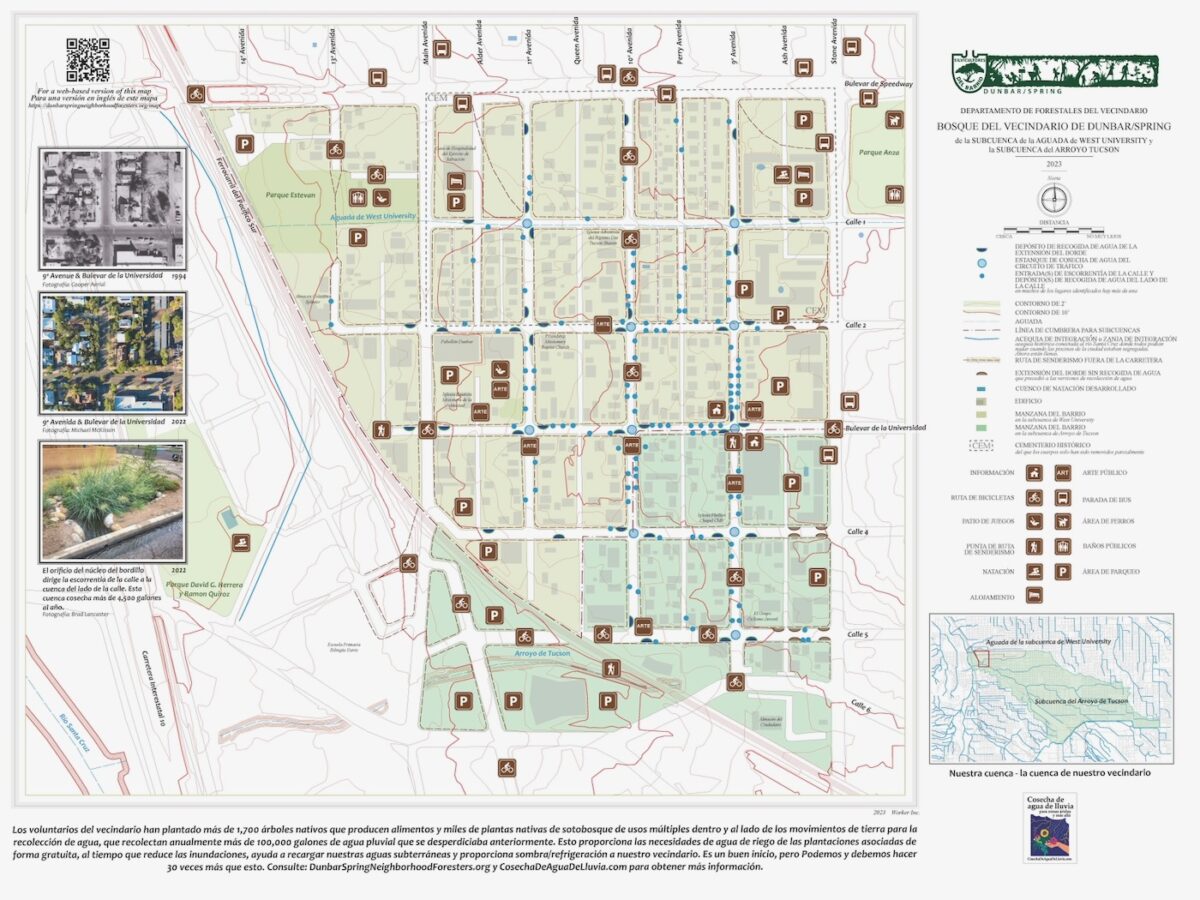

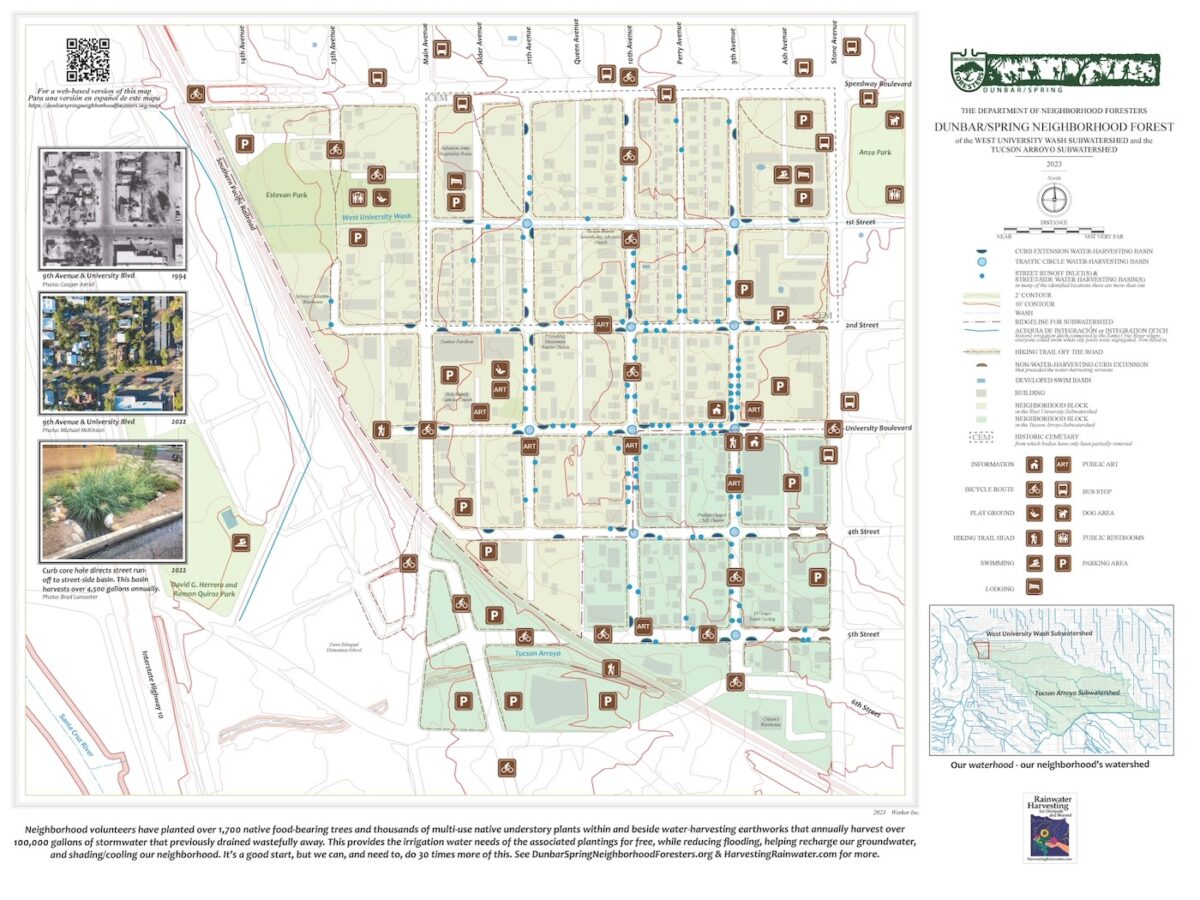

Download and/or view a high-resolution 2023 version of the map

Then zoom in to see the details.

Compare the 2023 version of the map to the originally released 2022 version (below)

to see how the map is evolving and the amount of water harvesting is growing.

Download the 2022 version of the map

View a full-size image of the 2022 version of the map

Descargar y/o ver una versión en español del mapa

This map highlights the locations of our neighborhood’s growing & evolving green infrastructure (water harvesting and rain-irrigated native food forestry) and other amenities, borrowing graphics/symbols from the National Forest Service and National Parks in hopes that readers look at our community in a different way, focusing more on its myriad life and what enables it.

We can all help grow and steward national neighborhood parks and neighborhood forests right outside our doors where we live, work, and play; and do so in a way that once established, they are irrigated solely by free on-site waters such as rain, stormwater, greywater, etc. in a way that reduces flooding while helping recharge (or give back to) our groundwater, streams, and rivers, rather than extract from them, so that our individual, community, and planetary health all improve together. See here for a number of the ways we do so.

As of summer 2023, our neighborhood has 190 street-side street-runoff-harvesting rain gardens (1o more than in 2022). We’ve planted over 1,700 native food-bearing trees, thousands of multi-use native understory plants, and our street-side and in-street rain gardens annually harvest over one million gallons of stromwater, which previously wastefully drained away. But we can, and need to, do 30 times more of this.

The map also highlights what may need to be changed or evolved. The crazy amount of sun-baked parking lots in our neighborhood is such an example, as their exposed asphalt is contributing to the heat-island effect raising temperatures in our community, and dehydrating it. The stormwater runoff from those parking lots could be redirected from stormdrains to storm-harvesting rain gardens within and around the parking lots to freely irrigate native shade trees that would grow to shade and cool the asphalt, while controlling flooding and generating many other amenities. See here for examples.

Historical elements

Santa Cruz River

The Santa Cruz River used to run year round on the west side of Dunbar/Spring and downtown Tucson before that flow was killed from mechanical pumps extracting groundwater at a rate that exceeded natural recharge. Natural recharge of the groundwater was also dramatically reduced by the removal of the vegetative sponge (such as mesquite bosques or forests and wetlands) that used to line the Santa Cruz River, and replacing them with water-draining pavement, buildings, and compact bare earth.

Acequias or irrigation ditches

When the river flowed there were many pre-historic and historic irrigation ditches, or “acequias” that would spread the river’s flow over fields within the river’s floodplain.

Acequia de integración or Integration Ditch

Barrio Anita just west of the Dunbar/Spring neighborhood, used to be along the eastern bank of the Santa Cruz River before construction of the I-10 highway severed that connection. Through the 1940s Barrio Anita also had an irrigation ditch connected to the river. The community named the ditch “Acequia de integración”, or “Integration Ditch” because it was a place that brought everyone together, and all were welcome to swim; regardless of their ethnicity, beliefs, of the color of their skin. The acequia was a welcoming oasis when city pools, such as Oury Pool in the David G. Herrera and Ramon Quiroz Park were segregated.

Sonora sucker fish and the water-harvesting horned lizard

When the Santa Cruz River flowed you could walk less than a half mile from the Dunbar/Spring neighborhood to the river, take a swim, and fish your dinner. The sculpture, in photo below, of the native Sonora sucker fish (which would grow up to 14-inches long) and Texas horned lizard symbolizes some of this past and our potential.

Blue arrow denotes stormwater flow.

The Sonora suckerfish were once abundant in the Santa Cruz River, but by 1937, were extinct from the dwindling flow caused by excessive groundwater pumping.

While the horned lizard has adapted to our dry climate by harvesting rainwater off its back and directing it to its mouth via gutter-like channels between its scales.

We too, need to harvest rainwater from our “backs”, roofs, roads, and walkways to regrow the absorbent living sponge and regeneratively give back more water to our Place and the larger watershed than we take.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 2019, reproduced with permission from Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition.

Court Street Cemetery

As many as 8,900 bodies may be buried in the Court Street Cemetery bounded by Speedway Blvd, 2nd Street, Stone Ave., and Main Ave. It was in operation from 1875 to 1909, and while the tombstones were moved to develop the neighborhood, the bodies never were. So it is not uncommon that we come upon a rotted casket and skeleton when we dig holes for water-harvesting basins and trees. When the digging is easier, you are likely close to reconnecting with the past.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Inspirations

Tenderloin National Forest

The Tenderloin National Forest exists within a dead end urban alley in the Tenderloin neighborhood in San Francisco, CA. It used to be bare asphalt with lots of dumpsters and strewn about garbage, but community activist Darryl Smith envisioned more. Along with other activists, he broke through the asphalt and planted a native redwood tree at the end of the alley. More plantings followed, along with beautiful murals, an earthen oven, performance space, hand-placed cobblestone, a neighborhood map (utilizing national forest and national park graphics), and the co-founding of the adjoining Luggage Store Gallery, a nonprofit arts organization, with Laurie Lazer. Luggage Store Gallery leases the now decommissioned alley from the City for $1/year and works closely with the community to evolve and steward this special place.

REFERENCES:

Un Camino al Río: Recuerdos del Río Santa Cruz y Barrio Anita

A Path to the River: Memories of the Santa Cruz River and Barrio Anita by children and neighbors from Barrio Anita, A Path to the River Press, 2000.

“The Mystery of the Wet Lizards: Why Do They Stand Like That…and in the Rain?” by Charline Profiri and Wade C. Sherbrooke

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition by Brad Lancaster. Rainsource Press, 2019.

What do you think?

This map is a second draft. Let us know what you think.

What works for you? What doesn’t? and Why?

How might we improve this map and what it strives to convey and inspire?

You can email your responses to NeighborhoodForesters@gmail.com.

For more photos, projects, history, and information on the Dunbar Spring Neighborhood Foresters

See here.

Thanks to the map’s creators

This map was created though a collaboration with Bill Mackey of Worker Inc., the Dunbar/Spring Neighborhood Foresters, and Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond.

Help us help others

If you’d like to support the Neighborhood Foresters in the creation of such educational graphics, its on-the-ground planting and stewarding of rain and native food forests in the public rights-of-ways, and the generation of tools/events/policy to help others please consider making a donation here.