This site focuses on the efforts of the Dunbar/Spring Neighborhood Foresters in Tucson, Arizona. But it is meant as a resource for anyone, any neighborhood; and their efforts in growing more reciprocal life.

It’s an invitation for anyone to participate—see our Events, Sign Up, and Be A Neighborhood Forester pages. And we hope that it inspires and aids neighbor- and neighborhood-led forestry efforts everywhere. See here for the Neighborhood Foresters’ aims & goals.

Since 1996 we’ve collaborated with our neighbors to plant over 1,700 native food- and medicine-bearing native trees and thousands of multi-use native understory plants (the plants growing under the overstory or canopy of the trees).

And we’ve collaborated to plant over a million gallons of stormwater annually in the neighborhood’s public rights-of-ways via water-harvesting earthworks or rain gardens that freely irrigate these plantings while also reducing downstream flooding.

For more of what we do, and you can too—see links below or scroll

• Growing neighborhood forests

• Growing neighborhood foresters

• Planting rain, plants, & community capacity

• Planting native seeds with the rains

• Growing & harvesting wild foods

• Growing wildlife habitat & diversity

• Stewarding the forest & its foresters

Growing neighborhood forests

Tucson is the third fastest warming city in the U.S., but we can reduce urban temperatures by over 10˚ F degrees in the shade of native vegetation.

By planting the rain and multi-use native vegetation, hot and exposed public rights-of-ways can become cool and shaded, food-producing public forests that shelter and enhance public walkways and streets (see figures 2A, B and figures 3A, B).

Stormwater running off the streets in turn becomes a free irrigation source for the forest by directing the water to the street-side plantings via curb cuts and curb cores. This practice also reduces downstream flooding, naturally filters pollutants, and helps recharge our groundwater.

Barren public right-of-way draining stormwater to the street 1994. Blue arrows denote water flow.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster.

Vibrant public forest harvesting street runoff to grow shade for the public walkway and street.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster.

Blue arrows denote stormwater flow lost to the street.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Shaded public walkway full of life.

Blue arrows denote stormwater flow into water-harvesting, vegetated basins.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Our local actions have global consequences.

The following is reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster…

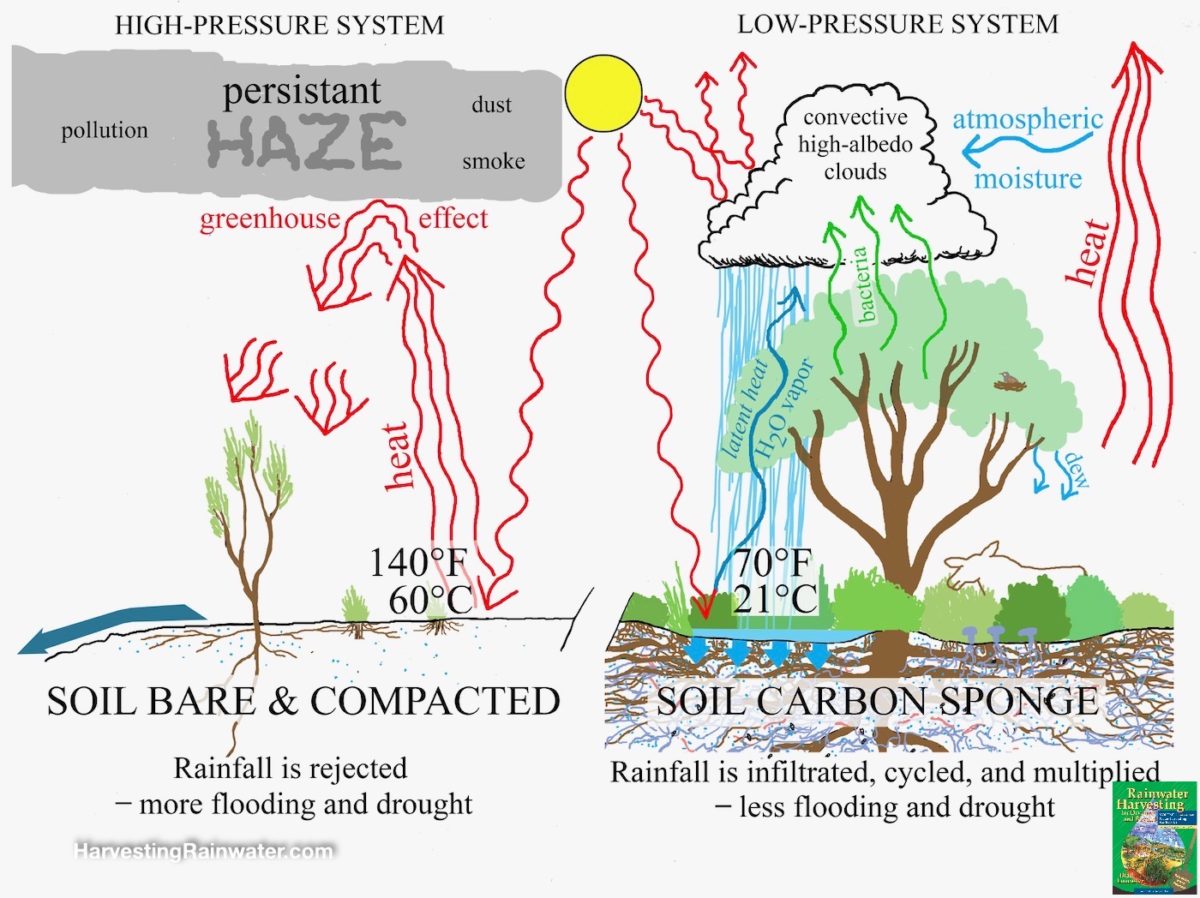

“There is a powerful, beneficial partnership between the planet’s hydrologic cycle circulating life-giving water and the carbon-based, soil-building, and carbon-cycling life in the soil—known as the soil-carbon sponge. According to climate scientist and soil microbiologist Walter Jehne, the vast majority of the heat dynamics and hydrologic cooling on Earth is governed by our planet’s hydrologic cycle. And that cycle, coupled with the soil-carbon sponge, helps maintain a stable climate on our planet such that the amount of heat released to space is equal to incoming heat from the sun—though our planet has been holding onto more heat than it releases since about 1750 due to human-influenced climate change, and the destruction of the soil-carbon sponge.”

The condition of the soil-carbon-sponge controls the fate of rainfall and affects climate. Adapted from “Recognizing the Soil Sponge” by Peter Donovan, SoilCarbonCoalition.org.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition”

Neighborhood forestry, as we advocate, regrows the soil-carbon-sponge and enhances the hydrologic cycle, improving the climate for all.

For more on how we plant rain, forests, and the soil-carbon-sponge—and how you can do likewise—see…

• Neighborhood Rain, Tree, & Understory Plantings

Growing neighborhood foresters

We are often told the city does not have the money to plant and maintain enough vegetation to truly shade our neighborhoods. Individual citizens sometimes say they don’t have the skill, physical ability, or knowledge to plant and care for a tree.

So, we work with these neighbors and others to plant rain and hardy native trees and understory plants; and then steward those plantings. That way, those who live closest to their section of the neighborhood forest, and who care most about it, are able to well take care of the forest they help plant and love.

Our hands-on Work & Learn Stewarding Parties offer many different opportunities to gain new skills and experience as you help enhance sections of the neighborhood forest. It’s also a great opportunity to get to know more of your neighbors and folks from neighboring neighborhoods as we help each other out. We plan these parties around neighbors and areas of the neighborhood forest needing help. See figures 4A-F below for progressive work done in a water-harvesting and pruning & mulching Work & Learn Stewarding Party…

Blue arrows denote stormwater flow lost to the street.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Blue arrows denote water flow.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

For more info on Growing Foresters…

• Sign up with us to be notified of Neighborhood Forester events in Tucson, Arizona

• Check out our Be a Neighborhood Forester page for our Aims & Goals, Origins, Regular Events, and more

• Check out our Four Levels of Neighborhood Foresters page for different levels of commitment and support

Planting rain, plants, & community capacity

Planting the rain is done on different scales based on the site, the available resources, and the needs.

Our annual Neighborhood Rain, Tree, and Understory Plantings plant a much higher volume of water and vegetation per basin than a Work & Learn party in a way that makes a greater number of plantings regenerative (giving back more resources than they consume) as opposed to degenerative (consuming more resources than they generate). So, rain alone can provide all irrigation needs of more associated plantings once they are established, while also reducing downstream flooding.

On average, over 1 million gallons of rain falls in a year on every one-mile length of neighborhood street in Tucson. That is enough water to sustain over 400 native, low-water-use trees per mile, or one tree every 25 feet on both sides of the street—if we direct that water to street-side basins instead of the storm drain. By doing so, we can sustainably grow a continuous canopy of shade on both sides of the street; while also helping recharge, rather than deplete, our groundwater.*

* “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

At our our annual Neighborhood Rain, Tree, and Understory Plantings we work with city officials to permit, and local contractors to excavate, the high-volume planting basins (averaging 8’ long x 5’ wide x 1’ deep), which on average can each harvest over 4,500-gallons of stormwater per year. As part of this work, the contractors also haul away the excavated soil, do the bank-stabilizing rockwork, create planting terraces, and drill core holes in the street curb to direct street runoff to the street-side basins. By working with this team we help build understanding and capacity among city staff and commercial contractors and crews to help create, rain-irrigated native food forests in our neighborhood and all others where they may then work. Over the years we’ve also worked with city staff to streamline the permitting process for neighborhood foresters/volunteers to coordinate such plantings.

And by coordinating work among multiple sites in the neighborhood we are able to bring down costs for all, and also provide additional services while the contractors and their equipment are here—such as removal of barriers to pedestrian access in public pathways, such as loose gravel and landscape mounds.

We train and coordinate volunteer planting crews to plant the basins. The adjoining property owners agree to steward these plantings, and Neighborhood Foresters’ Work & Learn Stewarding Parties and workshops help build their capacity to do so.

See here for more info on our annual Neighborhood Rain, Tree, and Understory Plantings and how you too can organize one.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

Blue arrow denotes street runoff flow into basin via curb core.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

For some hands-on experience

• Sign up to be notified of our events

Planting native seeds with the rains

Perhaps the cheapest and easiest way to plant is to plant native seeds within or beside water-harvesting earthworks or rain gardens at the beginning of the rainy season. If there is enough rain the seeds will germinate and grow. If there is not enough rain, they’ll lay dormant until conditions are right to grow. Planting within or beside water-harvesting earthworks dramatically increases germination rates of the seeds and growth of the seedlings thanks to the extra water these earthworks provide.

And as the in-situ-grown plants grow, their roots expand further than nursery grown plants transplanted from pots, because their root growth was never hemmed in by a pot. The more extensive the root system, the stronger the plant in wind and drought, and the more moisture it can access.

We give free native seed to those volunteering at our neighborhood forester events so they can plant their sections of the neighborhood – and we also help with those seed plantings as requested.

We also help with plant identification, have posted native wildflower signs in the neighborhood, and organize Work & Learn weeding parties so desired native wildflower and other plants dominate, reseed, and expand as opposed to undesired invasive weeds.

Find out more in our Planting Guide and Work & Learn stewarding parties

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Blue arrows denote stormwater flow into planting areas.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

For some hands-on experience

• Sign up to be notified of our events

Growing & harvesting wild foods

There are over 400 food plants native to the Sonoran Desert. We plant many of these within our neighborhood forest to grow food for people, livestock, and wildlife.

This also builds community and forges new friendships because the more time you are in the neighborhood’s public rights-of-ways—the more likely you are going to see, meet, talk to, and get to know your neighbors.

Taste before you pick because every tree has its own flavor of pods. If you like the flavor—keep picking. If you don’t like the flavor—go to a different tree. For best quality of pods harvest from the tree, not the ground; harvest ripe pods—they should snap in two if you try to bend them; and harvest BEFORE the rains (when ripe pods get wet invisible aflatoxins can grow on the pods).

Blue arrows denote street runoff flow into water-harvesting vegetated basins.

Photo: Jaime Chandler

Velvet mesquite leaves in lower left corner. Mesquite flour to left of bowl. Mesquite honey to right of bowl.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Blue arrows denote street runoff flow via a curb cut into vegetated water-harvesting basin.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Blue arrow denotes street runoff flow into basin.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

For native wild food plant identification and recipes see:

Ethnobotanical (Human Uses of Plants) Resources

To be notified of our various events including wild food processing sign up here

And check out www.DesertHarvesters.org

Do you have photos of native foods harvests in our neighborhood and the resulting deliciousness that you’d like to share?

If so, email them to neighborhoodforesters@gmail.com and we’ll post them!

Growing wildlife habitat & diversity

Neighbor Maria Legarra who has lived in Dunbar/Spring since the 1966 told Brad Lancaster that in the late 1970s, the 1980s, and the early 1990s there were many sections of the neighborhood lacking trees and other vegetation, and that these areas were oddly quiet as there was no bird song. But now, grinning broadly, she tells me that bird song is abundant and getting more so still, thanks to all the Neighborhood Forester-organized plantings from 1996 to today—and the wildlife it attracts.

By planting a wide diversity of plants native to this area where we live, work, and play; we are able to bring the beauty and abundance of the Sonoran Desert to us here in the urban core. We don’t have to leave to find this life “out there.”

Instead, we are able to grow it right here—at home. Thus, home becomes richer and more alive.

After reforesting the once barren public right-of-way adjoining Brad and his brother Rodd’s property (see figures 2A – 3B at the top of this page) with native vegetation, dozens of species of native birds, pollinators, butterflies, and more returned to their regrown habitat.

Some of these birds travel thousands of miles each year to pay a visit as Tucson and our neighborhood is located along major migration paths. For example, the Wilson’s Warbler is a small bird that migrates from Central America to Alaska and back each year. And it needs to refuel along its journey. Our native mesquite trees are an oasis, because the Wilson’s Warbler can increase its body weight by 10 to 20% in just a couple of days of hanging out in a single velvet mesquite tree and feeding on the abundant insect life around it.

A native velvet mesquite tree supports over 60 species of native pollinators (which co-evolved with the native tree and its blooming times), while a non-native mesquite tree in Tucson only supports about a dozen native pollinators.

Solitary bees often sleep in the flowers at night which close up like a tucked-in blanket. There are about 1,000 species of native solitary bees in the Sonoran Desert. Let’s help grow, rather than destroy their habitat.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Cholla cactus grows great nesting sites for native birds in the urban environment because cats don’t climb cholla cactus. Flower buds surrounding the nesting dove are at the perfect stage for harvesting, but we’ll let her be.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

To learn how you can enhance wildlife habitat at home and in the neighborhood…

• Sign up to be notified of our events

• Sign up for Tucson Audubon’s Habitat at Home program

Enhancing Pedestrian Access

One of the many things that makes our neighborhood dynamic and unique is our wide public rights-of-ways and the growing diversity of sheltering and alluring life within them. So, we work with neighbors to remove barriers and enhance access for pedestrians of all ages along these public paths throughout our neighborhood. This way our neighborhood forest is inviting to all. See here for more examples.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

See below for the 2014…

To help improve pedestrian access…

• See here

• Sign up to be notified of our events

Stewarding the forest & its foresters

Hands-On Workshops

We offer twice a year hands-on workshops on pruning and mulching taught by certified arborists. Workshops are open to everyone. And we learn by doing as we help prune sections of the neighborhood forest needing pruning and mulching. We then return to these areas year after year to observe and learn from the effects of our past pruning. Continuing Education Credits available.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Hands-On Work & Learn stewarding parties and their support crews

We prioritize where we hold our Work & Learn stewarding parties (pruning, mulching, planting, weeding, enhancing pedestrian access, etc) where the work needs to be done in the neighborhood and where there is a neighbor or two in that part of the neighborhood willing to help organize the stewarding party.

Similarly, we support Neighborhood Foresters who have stepped up to regularly steward their section of the neighborhood forest (could be as little as a round-a-bout or as big as a one-block stretch of public right-of-way). A big way we do this is with volunteer crews we bring out to help that Neighborhood Forester.

That way we help each other as we help the larger community.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Tool library

At our Work & Learn stewarding parties and workshops we lend tools from our tool library to those lacking tools.

Tools include hand bypass pruners, hand pruning saws, bypass loppers, pole saw, and pole loppers.

Neighborhood Foresters who have achieved Levels 2 and up can check out a professional-grade Neighborhood Forester pole saw and/or pole lopper from our tool library.

Neighborhood Forester rewards of tools, shirt, and more

For those committing to, and achieving one or all four levels of Neighborhood Forester you can pick from the following for each level of Forester you achieve:

• Neighborhood Forester-branded hand pruners and sheath,

• Neighborhood Forester pruning saw and sheath,

• tool sharpener,

• Neighborhood Forester stickers

• Neighborhood Foresters shirt,

• native wildflower and habitat restoration seed mixes,

• OR adolescent saguaro (providing a living totem and future harvests) to identify and support your stewarding efforts.

For more on how you can be a neighborhood forester, and be supported/stewarded…

• Sign up to be notified of our events

• Check out our Four Levels of Neighborhood Foresters page for different levels of commitment and support