Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

Plant the Rain—Simple Water Harvesting in the Landscape

by Brad Lancaster

Consider using storm water runoff to supplement, or even replace, your regular irrigation method. Runoff is a valuable resource often lost to the street, which also contributes to downstream flooding and erosion problems that are often acute in urban areas. Although a regular supplemental irrigation method (such as drip irrigation, drip buckets, or watering by hand-held hose) is needed for proper plant establishment and adequate early growth, using rain water can reduce the need for supplemental irrigation, lower water bills, leach growth-deterring salts from the soil, as well as furnish plants with natural nutrients and better quality water. Many desert plants (especially those native to the area), once established, can be weaned from supplemental irrigation entirely and still perform well if they capture adequate runoff.

Water harvesting includes “active” systems that collect runoff in a tank, the valve of which must be actively turned on or off to access the water. But “passive” water harvesting costs less and typically has a much greater capacity than active systems.

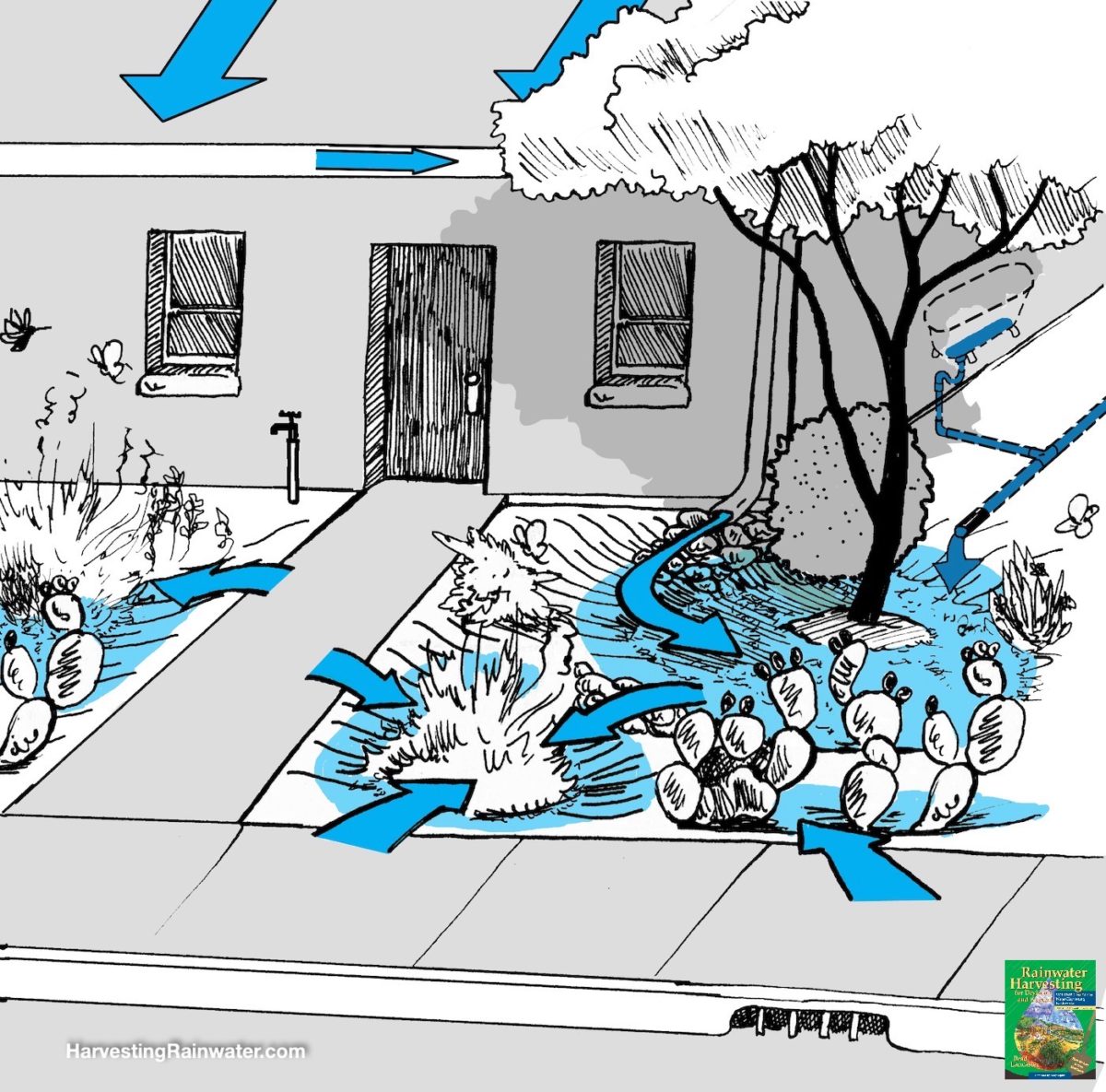

Passive water harvesting uses the soil as your living tank and the vegetation as your living pump. Passive water harvesting is the practice of directing and capturing, or slowing, runoff to water plants usually by simple soil grading (see figure 1). Done properly, one can capture and deliver a substantial amount of runoff to plants, even during fairly light rains. Basic techniques include swales (shallow channels), berms, (raised soil on the downslope side of the tree basin), and depressions or basins, often using rock to stabilize steep banks and a thick bed of organic-matter mulch as a moisture-conserving and soil-building sponge. Some combination of these can be applied in almost all landscapes, but best if designed at the planning stage. Using a builder’s tripod level, laser level, water tube level, or string level will ensure accuracy, but even a basic familiarity with runoff patterns is often enough to do the job.

Runoff from roof and sidewalk is directed to adjoining mulched and vegetated basins. In times of no rain, household greywater can be directed to same basins.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

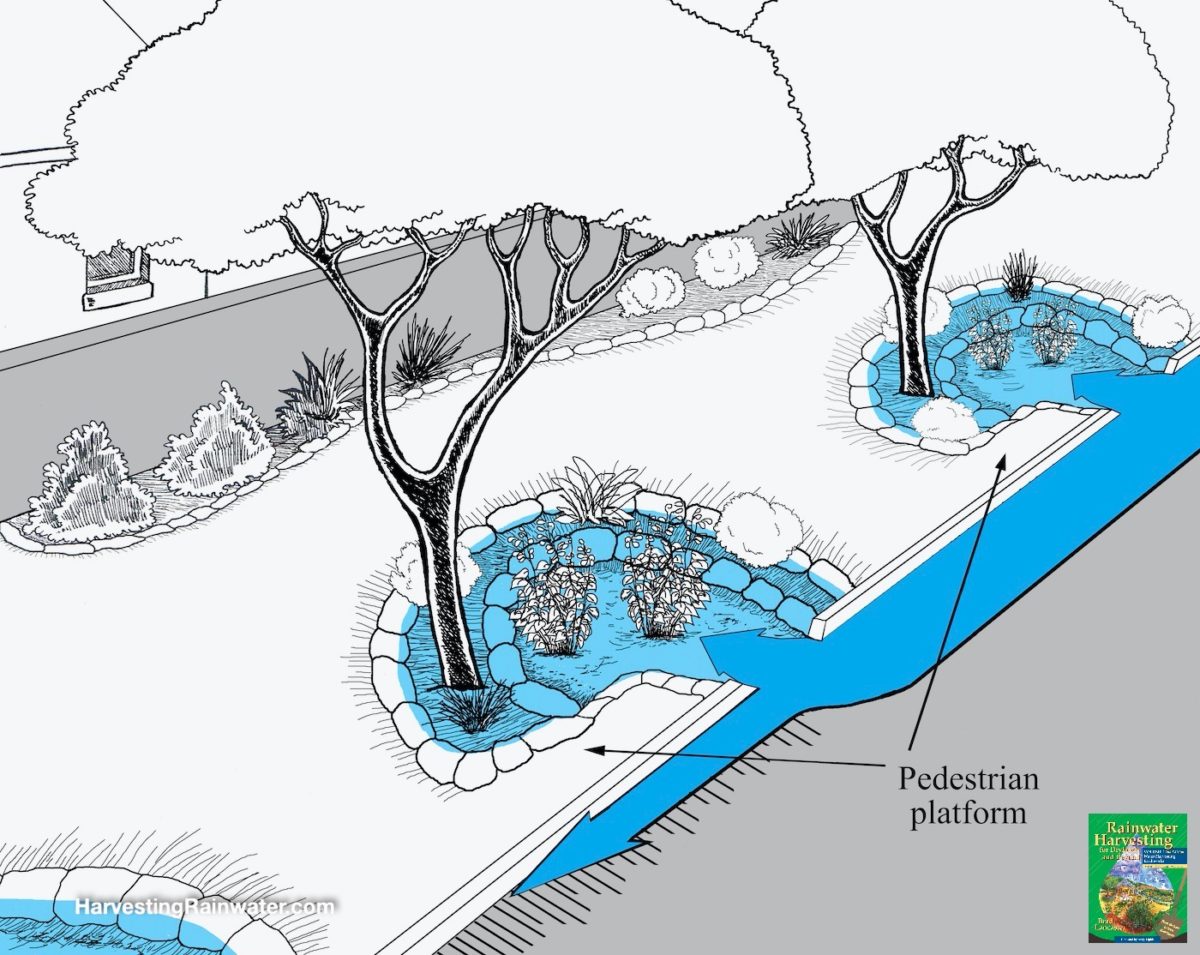

Figure 2 shows a row planting of trees along a conventional city street. In most cases adjacent property slopes toward the street, which is ideal for street tree plantings. In this example, the trees are planted on planting terraces with 12-inch deep, level-bottomed basins. The deeper the basin, the wiser it is to make the slopes of the basin more gradual, or to use rock-stablized terraces on the banks. Do NOT apply rock or gravel to the bottom of the basins as it will impede the infiltration of the water). Use a surface mulch of organic matter like fallen leaves, cut-up prunings (cut to 6-inch OR SHORTER pieces), compost, and/or wood chips on the bottom of your basin(s) and its planting terraces.

Minimum 2-foot wide pedestrian platform level with top of curb enables passengers exiting parallel parked cars to easily access path.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

The wider the basin the better – ideally the diameter of the basin is 1.5 to 3 times wider than the diameter of the mature canopy of the tree planted within it. This is because the roots uptake the majority of the harvested moisture beyond the drip line of their canopy. If you don’t have enough room to make such a wide basin, do what you can – a small basin or a number of small basins spread out around the plant is better than no basin. A building roof is a great potential source of additional runoff you can harvest within the basin.

There are other ways to direct and capture runoff for various planting arrangements through creative grading, but attention should be paid also to the land form character in the process. Grading for water harvesting should be considered an integral part of the landscape. It will be most satisfying if the grades contribute to the landscape form, as opposed to a system of ditches, furrows and rigid circular tree wells.

For more information on water-harvesting strategies see the full-color editions of the books:

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1 and 2 by Brad Lancaster and www.HarvestingRainwater.com.

For photos of water-harvesting work done at a Dunbar/Spring Neighborhood Foresters Work & Learn party see here

For photos of higher-capacity water-harvesting work done at one of our Annual Rain, Tree, and Understory Plantings

see here

For before and after photos of water-harvesting green infrastructure in the Dunbar/Spring Neighborhood

see here