by Brad Lancaster

The following is a re-posting of a blog I wrote in 2016 on my blog at www.HarvestingRainwater.com

A bare beginning

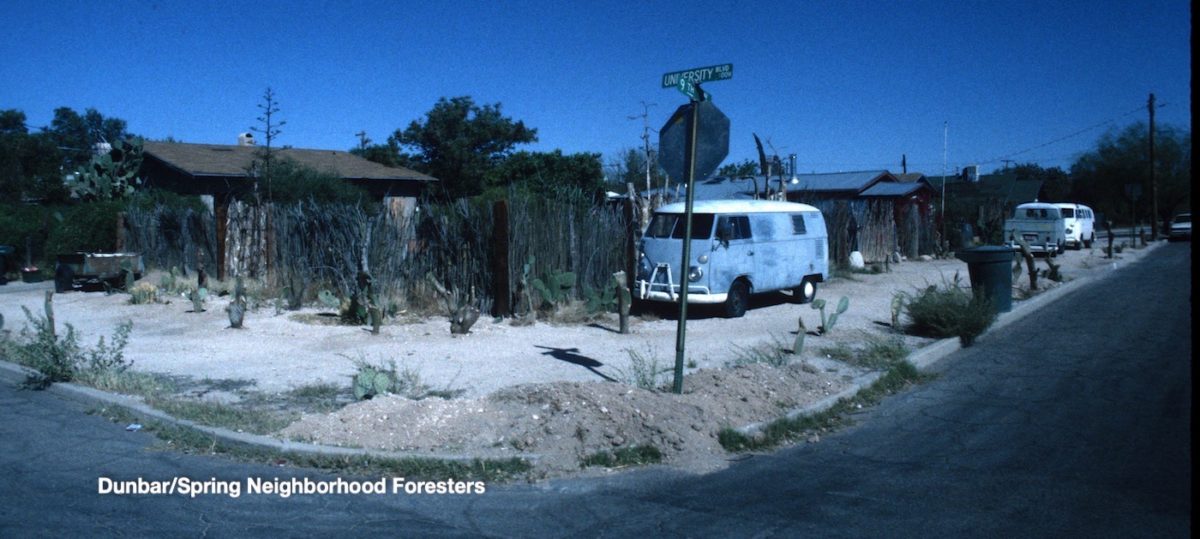

When I moved to the Dunbar/Spring neighborhood in 1994, many of the public rights-of-ways were not a pleasant place to walk.

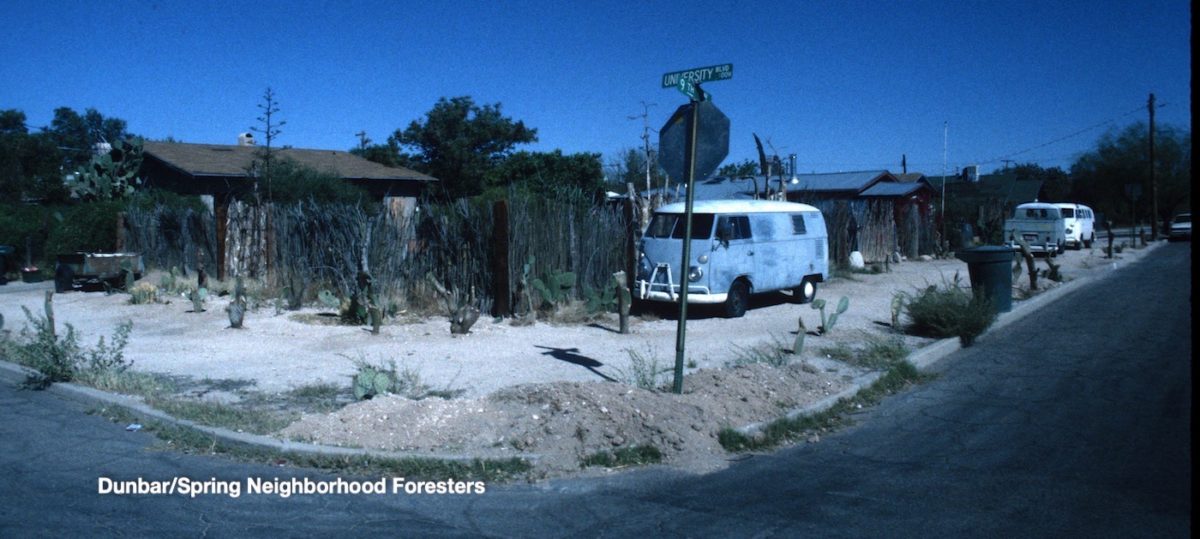

Most of the public rights-of-ways (the area between the street curb and property lines/fences) were hot, bare dirt, devoid of shade trees and other life. There were few sidewalks, but thankfully there was plenty of room for earthen footpaths. However, many people parked atop the footpaths rather than parking on the street—I’m afraid my brother and I were guilty of this, too (fig. 1A). This choice of parking location was driven partly by a fear that cars would get broken into if parked on the street. This fear was due in part to there not being many neighbors’ eyes on the street, which was due in part to having impassible footpaths—you did not want to hang out in or look out into the bleak street environment.

There was often high-speed cut-through traffic in the streets at this time.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

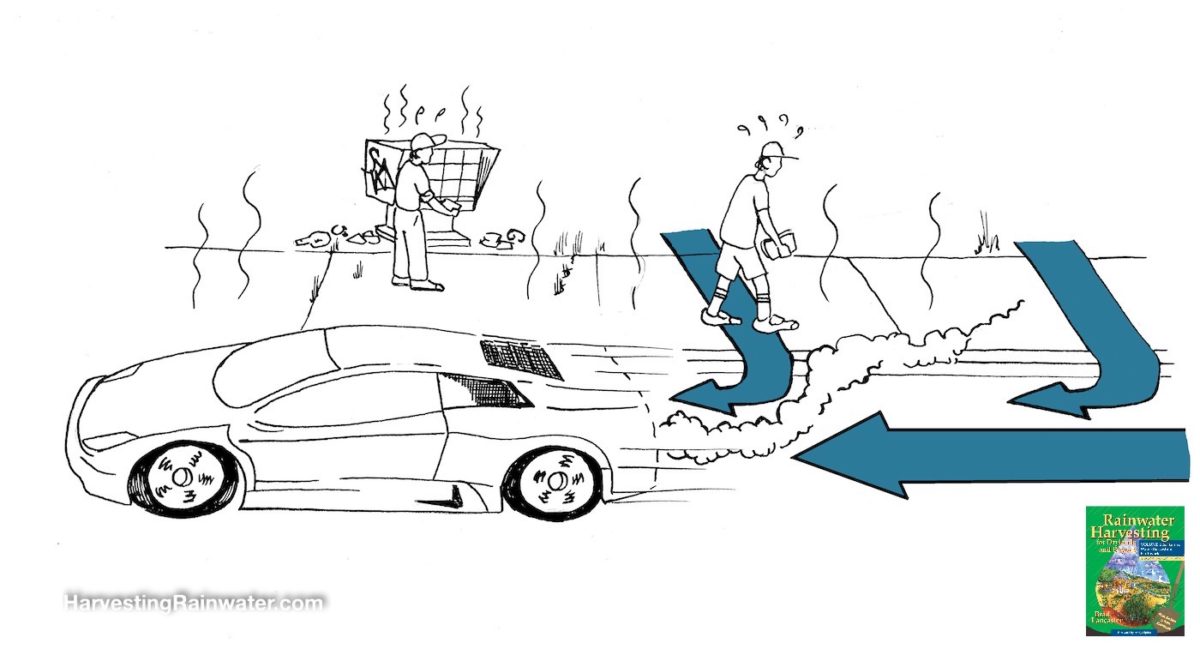

Yet another problem was the traffic in the streets. The neighborhood at that time was rife with speeding cut-through traffic (especially on the east-west streets) which would often collide with slower-moving pets or cars parked on the street. Thus I did not consider walking in the hot streets to be a viable alternative to walking in the rights-of-way.

Transformation

But there was much to love about the community, and a number of neighbors saw great potential for simple transformations of the negatives to positives, with the past and present sometimes informing the future. For example, before she passed away, Dunbar School alumna and activist Willie Fears told me that many decades ago when she was a child, trees lined Main Avenue and its footpath to downtown, enabling kids to walk there barefoot in summer from our neighborhood and back.

Those trees were all gone by the time I moved here, but an oasis could (and still can) be found on Perry Avenue between University Blvd and 2nd Street where South American mesquite trees planted by neighbors in the 1980s canopied over most of the street. Then-resident Steve Leal had obtained well over a hundred of these trees which volunteers planted around the neighborhood. Many of these trees were eventually lost as they blew over or were leaning so much they had to be removed. On the northwest corner of Perry and University Blvd grew (and still grows) a different tree, a huge native desert ironwood tree planted many years ago by Elizabeth Upham who had bought it from Target as a seedling in a one-gallon pot.

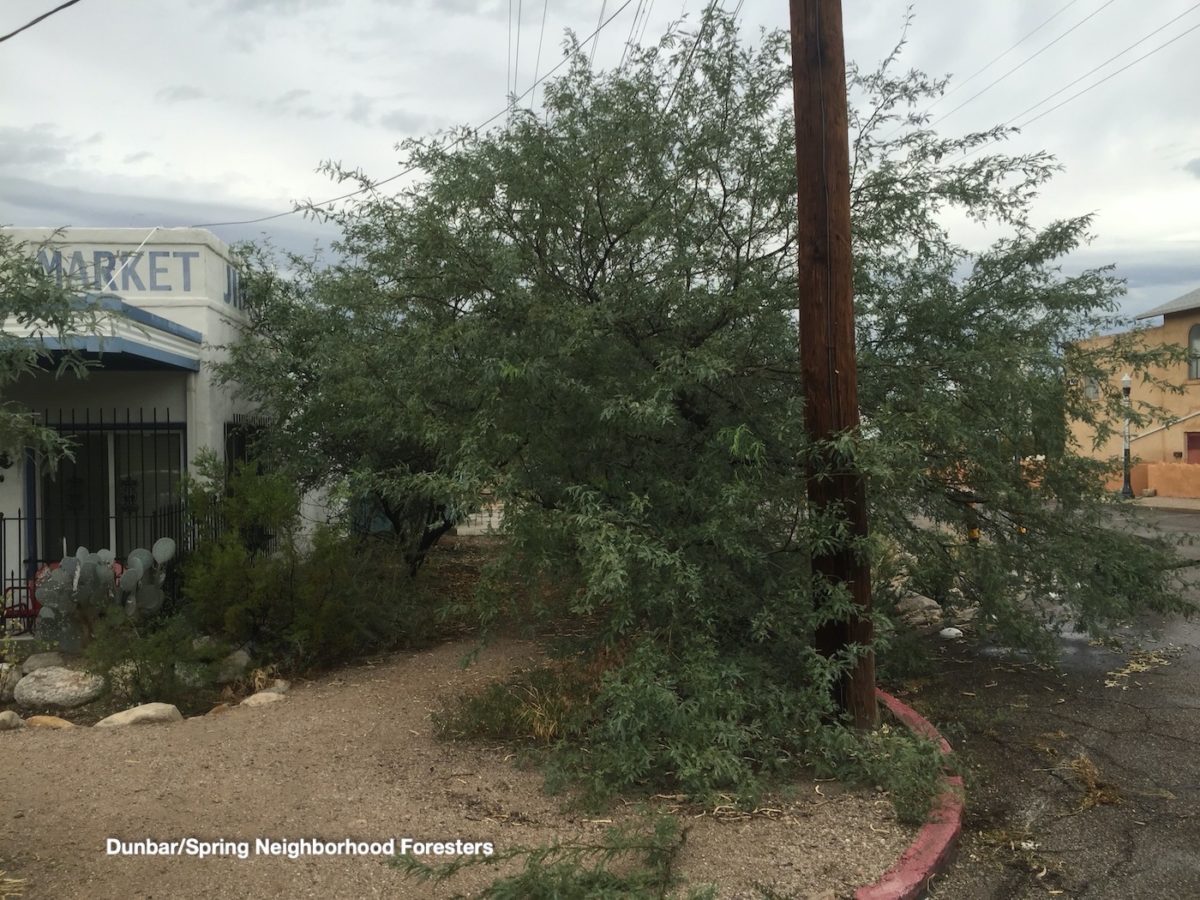

These and other tree stories and plantings inspired then-newcomers such as me, along with longer-term residents, to begin in 1996 what has become an annual neighborhood tree-planting project that brings neighbors together to plant native, food-bearing trees along our streets, walkways, and property lines. As we began to plant, we found cars moved to the street (figs. 2A and B) and the neighborhood immediately felt enhanced and more cared-for. Native songbirds, butterflies, and pollinators returned to the growing habitat. (We would later discover research showcasing how important native vegetation is for native wildlife. For example, native mesquite trees attract over 60 native pollinators, while non-native mesquites planted here attract only about a dozen.) More people started walking and bicycling in the neighborhood. Crime dropped.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Since 1996, our neighborhood’s annual tree-planting project has resulted in neighbors planting over 1,600 trees! Still more were planted before 1996, or since by individual efforts outside of the neighborhood programs.

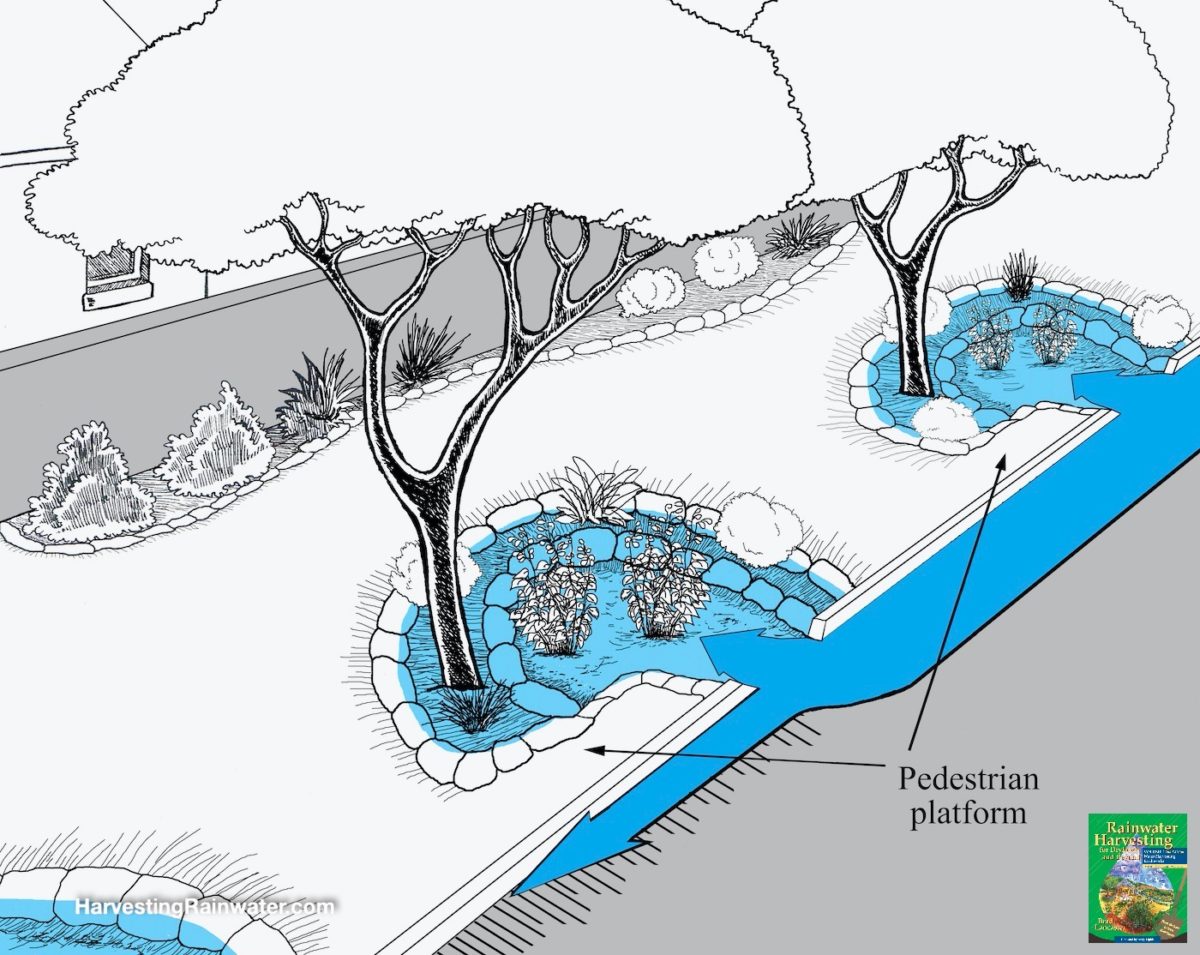

And those trees are doing particularly well where individual and/or neighborhood efforts are also passively harvesting rainwater and street runoff (while reducing downstream flooding). Over a million gallons of rain per year falls on a one-mile stretch of a typical Dunbar/Spring street. If that rainwater is directed to street-side basins as opposed to storm drains, there is enough street runoff along our streets to freely irrigate over 400 low-water-use native trees per mile, or one tree every twenty five feet, on both sides of the street.

Minimum 2-foot wide pedestrian platform level with top of curb enables passengers exiting parallel parked cars to easily access path.

Artist: Joe Marshall. Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

Beginning in 2004, my brother and I created pilot sites where we made illegal cuts or core holes in the street curb to enable the street runoff get to the street-side tree basins. Vegetation flourished. We dialogued with the city, and by 2007 the practice of cutting street curbs to harvest street runoff had been legalized, and was later even incentivized. Now legal curb cuts spread as pioneering neighbors such as the Jacobs and Turtle and Ian installed them on their blocks.

Interestingly, our neighborhood’s lack of sidewalks proved to be an asset in pioneering this street-runoff harvesting, as it allowed the neighborhood more leeway for making larger basins for stormwater and trees along the street than would’ve been possible if sidewalk placement had left a street-side planting area too narrow for effective stormwater harvesting. Additionally, we did not have the expense of cutting through and then repouring concrete sidewalks. We were also able to pioneer more naturalistic, slightly meandering, tree-canopied earthen footpaths.

In 2009 our neighborhood was awarded a $500,000 Neighborhood Reinvestment Grant for tree planting, rainwater and street-runoff harvesting, traffic calming, and public art—all in the public rights-of-ways, our public Commons. Thanks to that grant, individual efforts, previous small grants, and donations, by the year 2012 our neighborhood’s green infrastructure included:

- 10 water-harvesting traffic circles,

- 33 water-harvesting/traffic-calming chicanes

- Over 85 street-side basins fed by 50 curb cuts and 35 curb cores

All of this harvests over 700,000 gallons (2 acre-feet) per year of stormwater, which used to flood our streets.

Thanks to these growing and culminating efforts, there is now far more life in the neighborhood than there had been in the early 1990s (fig. 1B).

Thanks to tree planting, public art, and water-harvesting traffic calming, high-speed cut-through traffic in the streets has been dramatically reduced.

Compare to what it looked like before in figure 1A.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Same walkway as in figure 1B, but uninviting in 1998.

Same walkway as in figure 1B, but uninviting in 1998.Due to vehicles blocking path, lack of life, and full exposure to hot sun.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

An old challenge reappears in a new form

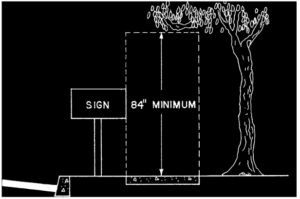

However, ironically, in some sections of the neighborhood’s public rights-of-way there is now so much life that it is once again becoming unpleasant or impossible to walk along the footpaths—this time due to vegetation blocking the route. Simple pruning can remedy this. Maintaining a minimum standard of a continuous clear walkway area, 5 feet wide by 7 feet tall, enables two people to comfortably walk side by side or pass one another (our neighborhood has mostly 20-foot-wide public rights-of-ways).

City standards for sidewalk and walkway clearance

City of Tucson Development Standard 3-01.4.0 (p. 278) states that sidewalks/walkways must have a minimum width of 5 feet and a minimum unobstructed vertical clearance of 84 inches (7 feet) (fig. 4).

Best times to prune

According to certified arborist Aleck MacKinnon, we can prune our native trees anytime here in the Sonoran Desert—especially if we need to remove a barrier such as a branch that is forcing people to duck while walking along a pathway.

But he says the least beneficial time is fall (October/November) since that’s when fungal spores are flying, increasing the likelihood of transmitting infection to the trees via open pruning wounds. Moreover the trees are not as actively growing, so their ability to seal off and heal the wounds will be delayed until the following spring.

Aleck says the best time for maintenance pruning of pathways, etc., is late spring (April/May) after the flush of spring growth. Such timing also allows trees to prepare for monsoon growth and get the best bang for the buck when the rains come. Also, if you prune too early in the growing season you often end up with two sprouts where you tried to get rid of one.

Another good time to prune, as needed, is post-monsoon (August/September).

Additionally, Aleck notes, late winter (January/February), when leaves are gone, is the best time for structural pruning and young-tree and fruit-tree pruning, when you can more easily see the branches and help develop good structure before the growing season begins.

How to prune, while enhancing community

See here for a video on how to prune. See here for more.

However, some people don’t know how (or are not physically able) to prune, or are unmotivated.

To try to remedy these living barriers, the Dunbar/Spring neighborhood has organized free pruning workshops taught by certified arborists (such as Aleck MacKinnon, fig. 5), after which workshop participants and instructors all help prune sections of the neighborhood rights-of-way and their footpaths. The results have been wonderful, and the neighborhood has become more walkable (figs. 6 and 7). Still, there are still a number of areas with barriers that remain.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Turning “waste” prunings into an on-site fertility resource

As an additional incentive, we have made a chipping service available to chip up the green prunings into mulch (figs. 8A, B, C). This way none of the biomass and fertility leaves the neighborhood. This has been a reaction in part to the twice-per-year Brush and Bulky program, which just takes everything (fertile prunings included) to the dump. We wanted to play with transforming the Brush and Bulky waste streams into Chipped and Mulchy resource cycles.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Alternative to on-site chipping service

Due to the cost and time involved with renting and operating a chipper, we alternatively will haul prunings via a trailer to Tank’s Green Stuff where they turn the prunings into mulch and compost, then we will purchase mulch from them and bring that back in the trailer.

There is a free pruning workshop in Dunbar/Spring Saturday, October 1, 2016.

See here for more info.

Also, there is a chipping service to turn the prunings into mulch Sunday, October 2, 2016. See here for info on how Dunbar/Spring residents and businesses can register for the chipping service.

All of this doubles as preparation for our neighborhood tour on Sunday, October 16.

We, along with University of Arizona researcher Mitch Pavao Zuckerman, PhD, (fig. 9), have found the mulch helps to:

- Dramatically increase the rate of stormwater infiltration into the soil

- Reduce soil moisture lost to evaporation

- Reduce weed growth

- Increase soil life

- Naturally filter or bioremediate toxins from street runoff—basins mulched with organic matter were found to bioremediate over 10 times as many pollutants as an unmulched or rock-mulched soil in street-side basins, and

- Enhance the growth rate and health of associated perennial vegetation

In the early days, working with local non-profit Watershed Management Group, we got a grant to pay for a local landscape company to chip up the prunings. Though as of late, with grant money spent, neighbor/landscaper Omar Ore-Giron has been renting and operating a chipper after the workshop, charging a nominal fee (suggested $30 donation) to cover the cost of the equipment rental and some of his time. It is then up to those who requested the chipping to promptly distribute their resulting mulch within basins or around vegetation.

And of course one can hand-cut prunings into mulch with hand pruners or loppers (fig. 10). It is best to cut prunings into pieces 6 inches or shorter so the resulting mulch will look better, easily compact down, and beneficially decompose by maximizing soil-mulch contact. Prunings that are not cut up appear and act as brush piles.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

Different mulches for different places

Note that while the mulch from the chipper is great for water-harvesting basins, it is not appropriate for public footpaths because it is too coarse and can make walking more difficult for those with less-sure footing, those pushing baby carriages, or those in wheelchairs. My brother and I made the mistake of mulching the footpaths of the public right-of-way adjoining our properties with woody mulch that was too coarse (particle size up to 3 inches or more). It worked great for the soil and vegetation, but not accessibility. We mistakenly thought people walking on the coarse mulch would quickly break it up into finer pieces, but the coarse wood chips proved more resilient than we had anticipated. So we replaced the coarse mulch on the path with finer mulch (1/2-inch and smaller particle size) in time for our neighborhood’s home tour.

Good and bad path materials

The following materials on public paths were found to be barriers to public access:

- Loose rock or gravel

- Decomposed granite larger than 3/8-inch in particle size

- Course organic material (woodchip) mulch larger than 1 inch in size

- Broken concrete/sidewalks

Thus we ask that these materials be removed where needed to maintain a continuous 5-foot wide footpath in the public right-of-way.

Sloping or grading all pathways helps the path shed water, avoiding puddles on the path. Path runoff can be beneficially directed to adjoining lower-elevation planting basins.

The following path materials maintain public access:

- Compacted native soil—free and already on site!

- Screened organic-material mulch (woodchip) no larger than ½ inch in particle size. (Do not apply in a depth thicker than one inch. Thicker depths bog down wheels of carriages and wheelchairs). One supplier is Tank’s Green Stuff.

- Compacted or stabilized1/4- to 3/8-inch minus decomposed granite (DG). There are natural polymers that can be mixed in with the decomposed granite to hold it together better and stabilize it. DG is available from local landscape material suppliers. (Gary Wittwer, Landscape Architect for the City of Tucson Transportation Department, told me DG can be implemented to be American Disabilities Act (ADA)-accessible.)

- Pavers/brick, which can be installed within the grade/slope tolerances of the ADA

- Maintained concrete sidewalks (ADA-accessible)

A history of neighborhood resident-led efforts

For decades this neighborhood has been striving to enhance our individual health, safety, and make the community more walkable and bikeable with tree plantings, community prunings, traffic calming, public art, enhanced bike/pedestrian crossings of major streets, and festivals such as Porch Fest and the Mesquite Millings. Most recently our neighborhood worked with the Living Streets Alliance to do a Walkability Study for the neighborhood.

Other community-planning endeavors have included:

- the Stone Avenue Corridor: Measures for a Livable Corridor

- the Building Bridges Project

- The Dunbar/Spring Community Development Plan in 1995

- The purchase of the Dunbar School in 1995 to create an African American Cultural Center and Museum. (Note that after the school closed in 1978, the neighborhood fought a proposal to turn it into a jail for DUI offenders.)

- The creation of the John Spring Neighborhood Historic District in 1989.

…Which brings us to the present

Looking back 10 and 20 years, it is amazing how much more greenery, bird life, beauty, food, and shade we now have in the public realm of this neighborhood. Coupled with this is a dramatic increase in people walking, running, and cycling through the Dunbar/Spring community, which very often results in community-building, face-to-face interactions where people slow down and stop to talk. This contributed to the city’s decision to reclassify University Blvd, and parts of 9th Ave and 10th Ave from higher-speed, higher auto-traffic streets to bicycle boulevards.

All this has inspired many other neighborhoods and communities (in Tucson and beyond). I’m grateful for this transformation, and I’m grateful for all the neighbors who helped make it happen. Momentum for so many of these efforts was generated from the questions, “What kind of community do we want to live in, and how can we help make that happen?” And, “What potential, already inherent in the neighborhood, can we partner with?”

Artist: Joe Marshall. Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

Artist: Joe Marshall. Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition” by Brad Lancaster

This neighborhood’s evolution is neither perfect nor complete. Evolution and change are constants. But we can consciously strive to evolve in the direction we desire in a caring way that enhances life and health for ourselves, our neighbors, and the larger community. Many of us have been trying to do so for years, and we can aim to get better still.

…And the very near future

Saturday, October 29, 2016, will be our neighborhood’s 21st annual tree planting.

Check our neighborhood website and this website for upcoming details, and come plant with us!

We plan to have two free pruning workshops per year in the neighborhood, aligned both with certified arborists’ recommendations for best pruning times, and with the typical times of greatest need for pruning: One in late winter (February), and one in late summer (August/September).

The day after each we’ll offer a chipping service to turn the prunings, otherwise wasted, into beneficial mulch. Please join us! As always, the pruning workshops are open to anyone and everyone. Invite friends and family, whatever neighborhood they live in.

Check back to this website’s calendar of events closer to the pruning times for more info.

As to planting the rain, fertility, community, and more, you can get your hands on, read, and implement the strategies in my award-winning book series, Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond.